It’s almost thirty years since I trained up as a CBT instructor. As part of the second ‘classroom’ session – officially known as ‘Element D: on-road preparation’ – we had to attempt to prepare our novice riders to cope with the on-road element…

…all in about 30 to 40 minutes.

One issue we had to cover was to explain that motorcyclists run a significant risk of not being seen by other road users. The ‘looked but failed to see’ error is so common it has its own abbreviation in research literature (LBFTS). I’m sure it’s old hat to regular readers of my pages, but for a new riders it can be hard to comprehend.

So what was the DVSA’s guidance to us instructors? ? Essentially, we were supposed to tell trainees that they were to make themselves easier to be seen; we had to explain the use of conspicuity aids, the differences between daytime fluorescent clothing and night-time reflective kit, and why they should use dipped (low beam) headlights in day time (day-riding lights).

It all began with the first ‘Ride Bright’ campaigns in London in the mid-70s. Many riders voluntarily adopted hi-vis clothing – I was one. Most turned their lights on too – me included when I graduated to a bike with a decent alternator. In fact, motorcycles have had their headlights wired permanently on for over fifteen years.

Just one problem. There is no evidence of positive results.

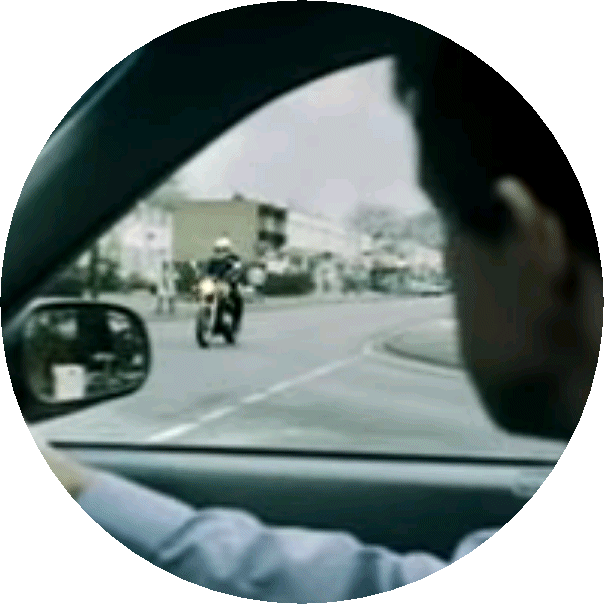

Drivers turning at junctions still look, then fail to spot an approaching motorcycle. And the ‘Sorry Mate I Didn’t See You’ collision with another vehicle at an intersection remains the most common crash involving a motorcyclist. The photo is clipped from the mid-70s ‘Think Once, Think Twice, Think BIKE!’ public information film, incidentally.

Why?

Here’s my guess. There’s an unintentional subtext to all the ‘Think Bike’ campaigns that we have been having since the mid 1970s. In telling new riders to “make yourself easier to see”, the subtext is this – when we encounter another vehicle at a junction ‘the other fellow’ is RESPONSIBLE for LOOKING FOR US.

And if they don’t see us and a collision occurs?

Then they ARE NOT DOING THEIR job – they must be incompetent or inattentive.

Worse, thanks to the ‘make yourself conspicuous’ messaging, riders come to believe that if they use conspicuity aids, they WILL be seen. Believing that, they don’t pay attention to the potential crash that’s being set up for them. Then when a driver commits the ‘looked but failed to see’ error and turns into the path of the approaching motorcycle, the rider sees what’s happening too late and is caught by SURPRISE! And thus riders fail to get out of collisions that could have been avoidable if only the rider had sounded the horn, then braked or swerved, promptly.

“The driver should have seen me” is all too common as a post-crash refrain.

As I’ve been saying for more than two decades – based on my own decade and a half of dodging vans and taxis in London – telling the driver to look out for bikers is only one-half of the story; far more often than not, the rider sees the turning vehicle – or at least the point at which it will appear – well BEFORE the collision becomes inevitable.

It’s this awareness of the need to search out the potential for a SMIDSY collision before it happens, and to understand what to do to stay out of trouble is what underpins the ‘No Surprise? No Accident!’ concept.

That’s why back in 2012 I delivered the very first Science Of Being Seen (SOBS) presentation at the pilot Biker Down course in Kent. Rather than say “wear hi-vis and ride with your lights on so drivers see you”, SOBS took a rather different look at conspicuity aids – explaining why sometimes they DON’T work:

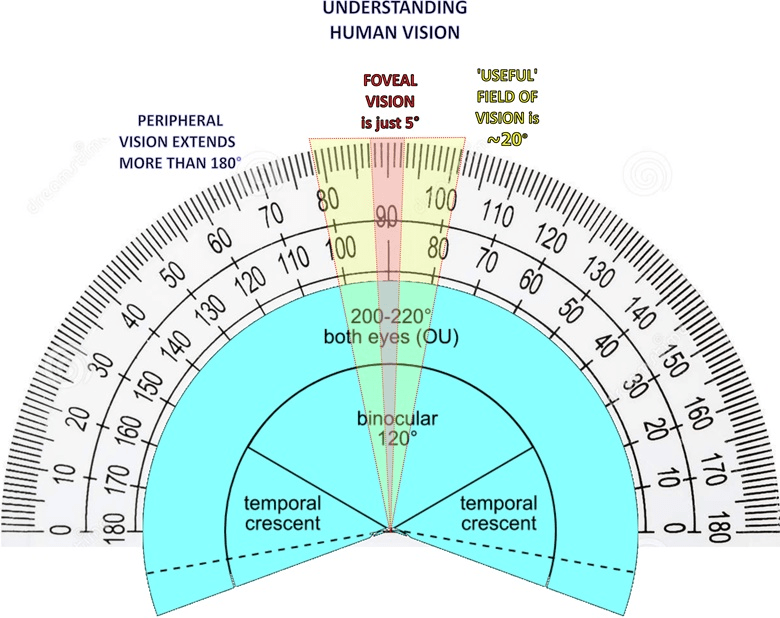

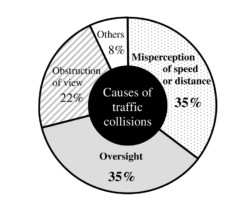

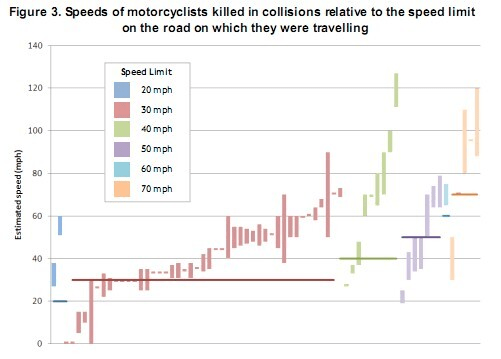

:: looked but COULD NOT see – the bike wasn’t where the driver was able to see it (accounts for around 1 in 5 collisions)

:: looked but FAILED TO see – the bike was visible but due to issues such as motion camouflage, saccadic masking and ineffective conspicuity strategies, the driver failed to detect it (the cause of around 1 in 3 collisions)

:: looked, SAW AND MISJUDGED – the bike was visible but drivers find it hard to accurately calculate ‘time to collision’ particularly on quicker roads (setting up another 1 in 3 collisions)

When we know WHY the collisions happen (and incidentally, distracted driving accounts for less than one in ten of the total, using a mobile at the wheel is about as likely to cause a SMIDSY as a medical emergency at the wheel), we can suggest some defensive measures.

The first is simple enough – ride where we can be seen, and be alert to moments we CANNOT be seen. We need to be aware of the effect of ‘Vision Blockers’ between our position and someone looking for us and to understand the driver blind spot issues caused by the vehicle structure itself. If we can’t be seen, no conspicuity aid will work.

Then and only then should we consider improved conspicuity strategies – I have suggested swapping Saturn yellow (the most common shade of hi-vis but a colour that’s a poor contrast with foliage in rural areas) with Pink for rural daytime use.

And finally I promote the use of proactive responses to a POTENTIAL threat from a vehicle that COULD be about to turn across the rider’s path including sounding the horn, slowing down, changing position and setting up the brakes. It’s not difficult – after all, there are only two things that a vehicle intending to turn into our path can do – wait till we’ve passed by. Or pull out.

So has this ‘protect yourself’ approach filtered down to other road safety campaigns?

Well, there are finally signs that just possibly it has. Back at the beginning of the month, Warwickshire Police announced their usual enforcement campaign, but also mention a new ‘Ride Craft Hub’ which:

“…will help riders identify a SMIDSY situation and protect themselves”.

And last week whilst searching for something else, I found that a couple of years back I’d reported on a story from Tasmania that shows another small but significant indication that the official attitude to rider training is slowly beginning to change.

Stating that the rate of motorcycle accidents in Tasmania had become too high, Infrastructure minister Rene Hidding said that initially the state rolled out more mandatory training “just as had been done in so many other places”.

But Ms Hidding continued:

”It became obvious that people in the industry knew [the process] was wrong.”

A Victoria-based trainer, Duncan McRae, was called in to create a new curriculum which he said was “built around educating riders about those five common crash types that we see most often”.

Does that sound like something you might have heard here?

So, small beginnings, but I believe we’re seeing indications of a shift towards the ‘No Surprise’ approach to riding.

I’m not saying we should stop telling drivers to ‘Think Bike’ as some seem to have assumed, but we should certainly start encouraging a ‘Biker THINK!’ mindset.

I do apologise if I seem to be banging the same drum, but until riders really do accept that SMIDSYs aren’t an automatic consequence of riding a bike, someone has to. And I’ll see what I can dig up on the background to the Tasmanian curriculum change. Watch out for that soon.

http://www.ridecrafthub.org/

http://www.scienceofbeingseen.org

http://www.nosurprise.org