[This post was originally written on October 11 2012 – which gives you an indication of just how long I’ve been talking about the problems of visual perception, motorcycle conspicuity in general and lighting issues more specifically. At the time of writing LED headlights were almost unheard of. So the article is about the use of LEDs for add-on auxiliary lighting which was becoming increasingly common at that time, rather than LEDs fitted as main riding lights. It’s been updated a little for clarity.]

At the end of my ‘Science of Being Seen’ conspicuity and collision avoidance presentation last night for ‘Biker Down’, a chap called Nick Ingram approached me to ask my views on LED light bars and how they might help, and he’s just sent me an online discussion, which I duly read.

The short version is that a lot of riders were positive about the current trend for fitting light bars, subscribing to the belief that “if one light is good, more must be better”.

But is that actually true?

As I said on Biker Down, anything that breaks up or distorts the silhouette of a motorcycle / rider means it takes observers longer to recognise that they are looking at a motorcycle, and in some circumstances they may not even recognise that what they are seeing actually IS a bike!

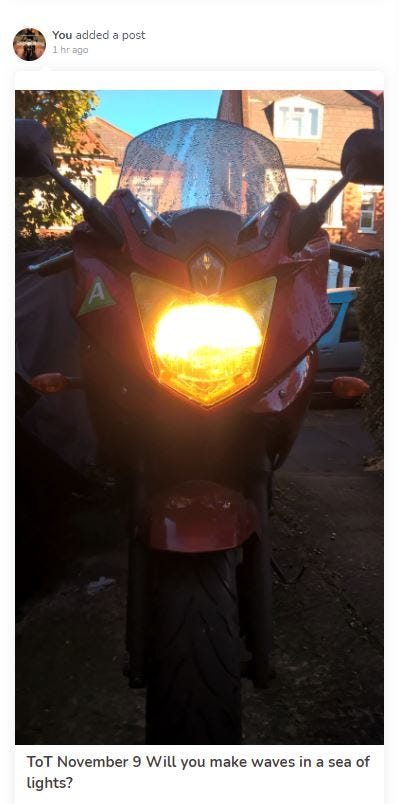

Have a look at the attached photo. Imagine we’re sitting in a side road looking at those lights coming towards us in the midst of a row of cars with headlights on.

We can see the lights, no problem. But WHAT exactly is it? WHERE exactly is it? How FAR away is it – if we don’t know what we’re looking at, we can’t judge distance. How LONG has we got before it gets here – if we can’t judge distance, we can’t make a judgement about speed either. Can we PULL OUT – without accurate speed / distance information, trying to work out ‘time to collision’ and whether we’ve a safe gap to pull out into becomes tricky.

What happens when the bike’s lights confuse the driver’s ‘recognition and range-finding’ system. Is he or she more or less likely to pull out?

The fact is we don’t simply know the answer to that question – it will depend on several issues such as whether the lights actually make us look further away, or whether the confusion delays – but does not CHANGE – the driver’s decision to go. This is the problem with any conspicuity aid – since they rely on the other road user detecting them, they MAY work….

…or they MAY NOT. And you and I will never know whether the driver who just waited for us as we rode by waited because he saw our extra lights… or whether spotted the bike regardless of the lights.

The bad news that we don’t know the effect on an approaching driver, the extra lights will change OUR behaviour. Behind the lights, we’re clearly hoping we reduce the chance of a driver pulling out on us, If we didn’t think that, why would we bother fitting them?

So the moment we fit extra lights “to be seen” – whether that’s for daytime riding or night riding – then we create a risk for ourselves; the BELIEF that the lights make it less likely that a driver will pull out in front of us.

Once we believe we’re easier to see, it’s likely we’ll start relying on those lights to keep us out of trouble. And then we’re more likely to be caught totally cold when the driver DOES pull out, all our lights notwithstanding.

So it would be really useful to know if additional lights worked.

Anecdotally, many riders report that fewer drivers pull out in front of them when using lights or wearing hi-vis. Unfortunately, it’s likely our perceptions are skewed because we’re no objective observers – when we want to see if the lights make a difference we’ll actually pay far more attention to what drivers do than we previously did. In the past, the incidents we’ll have noticed will have been the drivers who DIDN’T see us and pulled out, and not the far more numerous drivers who DID see us. So once we start looking to count ‘drivers who don’t pull out’, we’ll start noticing this far more numerous group than we had done previously.

What about safety studies? Some early studies purport to show riders using lights or hi-vis are involved in fewer accidents, but they are not ‘blind’ studies. They don’t send out random groups of riders who either have or don’t have lights fitted and switched on, but simply look at crashes. If riders who ride with lights on have fewer crashes, it’s entirely likely that the riders using day riding lights were aware of the conspicuity problem and thus more likely to have changed their riding style subtly and unconsciously to compensate for the risk.

So let me go back to a classic piece of work in the USA years ago in 1974 by a chap called Leonard. It was at the time that the debate on daytime lights was just starting. He created three different colour and lighting schemes, then compared the number of drivers who violated his right-of-way on a regular daily journey in which he alternated the use of a ‘control’ motorcycle and two ‘test’ motorcycles as follows:

• ‘Control’ – standard motorcycle with the headlight off

• ‘Lights only’ – standard motorcycle with the headlight turned on

• ‘Spectacular’ – motorcycle with extensive use of reflective materials, bright colours, lights

In 30 test days each riding the control motorcycle and the motorcycle with the headlight on he experienced respectively 1.9 and 1.8 violations per day, or when riding the control motorcycle and the ‘spectacular’ motorcycle 1.8 and 2.0 violations per day. In other words, the lights and the ‘spectacular’ colours made no difference.

He also tried riding a fake ‘police’ motorcycle to see what would happen. In 15 test days riding the ‘police’ motorcycle, Leonard experienced just one right-of-way violation. Make of that what you will!

[Edit – at time of writing, motorcycles in the UK had only just started to have permanently-on headlights, but it’s become more and more common. Has it made any difference to rider conspicuity? If it had, you’d expect that the proportion of junction collisions – compared with the total number of crashes – would have fallen. Updating this post at the end of 2021, I can’t see any such change in the crash stats.]

My conclusions? Our best defence is not to try to stand out from the crowd, but to ride in a way that not only accepts that drivers WILL make mistakes but to be able to DEAL with the situation WHEN, not if, it happens.